Introduction

Bob Adelman (American, 1930–2016), Box in Frank Robinson’s CORE Voter Registration Office, Sumter, South Carolina (detail), 1962, gelatin silver print, 7 3/16 x 10 1/2 inches, purchase with funds from the H.B. and Doris Massey Charitable Trust, 2007.176. © Bob Adelman/Magnum Photos

By Charles Johnson

Whenever we look at photographs of the civil rights movement, it is important to understand these powerful images in terms of this nation’s unique experiment in democracy. Half a century has passed since this nonviolent revolution transformed America, and viewers born after the 1960s might feel they are seeing images that record not just a different time but an entirely different world.

In order to properly appreciate these photographs, we must place them within the context of a 388-year struggle for justice and equality that began in 1619, the year twenty Africans were sold from a Dutch ship to colonists in the Jamestown colony. Those early arrivals from Africa became indentured servants—men like Emanuel Driggus, Anthony Johnson, and Francis Payne, who eventually purchased freedom for themselves and their families, amassed property, and established plantations. But soon enough those stolen from Africa during the Atlantic slave trade (the conservative estimate is 20 million people, but some scholars place the number as high as 100 million) found their condition of chattel bondage to be permanent and based on their race.

Although the Founding Fathers frequently described the evils of slavery when denouncing the treatment they had received from King George III, they were not prepared to abolish the profitable “peculiar institution” in their own colonies. Yet, as revolutionaries dedicated to Lockean liberalism and Enlightenment principles, they were able to transcend these contradictions and prejudices when they drafted the sacred texts of our civil religion—the Declaration of Independence and Bill of Rights—with “self-evident” truths that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” These inspiring, lofty ideals fueled the passion for freedom equally in blacks and whites.

That first revolution of 1776, and the cloudy, equivocal language of just four clauses in the Constitution (Articles I and IV), failed to extend freedom to black people and kept in place “the great sin and shame of slavery,” as Frederick Douglass called it. And so the fledgling American republic was plunged into civil war, a cataclysm that cost 620,000 lives, in an effort to correct the unfinished business of the Revolution.

Unfortunately, the Civil War, while freeing the slaves, did not close the gap between the nation’s democratic ideals and its practices. Many whites, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Abraham Lincoln among them, abhorred the obvious horrors of slavery but saw blacks as inferior and felt they should be repatriated to the American colony of Liberia and that America should remain a white man’s country. Furthermore, the newly freed slaves, propertyless and uneducated, were given scant assistance after their emancipation. “It was never intended that they [ex-slaves] should thenceforth be fed, clothed, educated and sheltered by the United States,” argued President Andrew Johnson when he vetoed Senate Bill 60, which would have given land to the freedmen. “The idea on which the slaves were assisted to freedom was that, on becoming free, they would be a self-sustaining population. Any legislation that shall imply that they are not expected to attain a self-sustaining condition must have a tendency injurious alike to their character and prospects.”

Expand image.

In other words, the former slaves were on their own. As the old black saying put it, they were expected to “make a way out of no way.” This would prove to be a difficult way indeed. For the next sixty years, between 1895—when Booker T. Washington delivered his famous proclamation that blacks and whites could “be separate but equal like the fingers on the hand” (which appeased the South)—and the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955, black Americans fell victim to a fragile, false, and ultimately doomed social and political arrangement: racial segregation, the American equivalent of South African apartheid.

In this publication and in the accompanying exhibition, pay close attention to the images of economic deprivation and systematic oppression—the run-down shacks blacks lived in, the “Colored” and “White” signs over drinking fountains preposterously different in size (fig. 1), and the disturbing presence of the Ku Klux Klan, whether marching openly in city streets or burning crosses in the dead of night. Clearly, separate did not mean equal. Worse, during the era of segregation, black Americans were systematically disenfranchised, denied gainful employment, refused access to the best education, denigrated in social situations, and relegated in every facet of civic life to second-class citizenship. A system as unjust and irrational as segregation, one that daily demonized and de-humanized black Americans, could only be sustained by social violence as great as that used during slavery. The world it created was Kafkaesque, and just as damaging to whites as it was to blacks, for whites were forced from childhood to believe in their innate superiority and to feel entitled by race to unearned privileges.

Yet another revolution, then, was required to address the unfinished business of the Civil War and Reconstruction. It began on December 1, 1955, when a 42-year-old seamstress and secretary of her local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) named Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white man in the black section of a crowded bus. Her non-cooperation with evil, as Thoreau would have called it, electrified and unified the 50,000 black men and women in Montgomery around an epic 382-day bus boycott spearheaded by the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), which elected to its presidency a 25-year-old minister named Martin Luther King Jr. He was a newly minted Ph.D. in theology from Boston University and the son of Martin Luther King Sr.—“Daddy King,” one of the most prominent activist-ministers in Atlanta. Serving at the helm of first the MIA and then the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), King and his lieutenants staged dramatic campaigns for desegregation and equality across the South for a decade, leaving his spiritual and moral vision indelibly imprinted on this third revolution to realize the nation’s most cherished principles.

Expand image.

Addressing five thousand people at the Holt Baptist Church during the Montgomery boycott, King thundered, “If you will protest courageously, and yet with dignity and Christian love, future historians will say, ‘There lived a great people—a black people—who injected new meaning and dignity into the veins of civilization.’” Often he said, “Christ gave us the goals and Mahatma Gandhi the tactics.” With his emphasis on nonviolence, on agape (unconditional love), and his belief in the “beloved community” as the ultimate goal Americans must strive for, young King guaranteed that black Americans would have the moral high ground when facing segregationists and white supremacists who had greater power and wealth. The movement’s leaders were far better prepared than their opponents. They had studied Gandhi’s tactics against the British in India. They knew history and the law. And they were aware that violence and bloodshed had characterized black revolts against oppression since the seventeenth century. Outnumbered ten to one, black Americans could never achieve freedom through armed struggle. But a nonviolent approach, with its grounding in the ideal of Christian brotherhood and the Declaration of Independence, gave this fresh phase of the black freedom struggle the character of a distinctly American revolution that all people of good will, black and white, had to acknowledge as the moral vision they preferred for themselves and their country, particularly during the Cold War, when the Soviets repeatedly criticized America for its treatment of black people.

These photographs show people of good will, inspired by the Montgomery boycott and the Supreme Court’s ruling in 1956 that segregation on buses was unconstitutional (and earlier by the Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka that school segregation violated the Constitution), who responded en masse to the most transformative domestic development in America in the twentieth century, often placing their own lives at risk. We know the leaders—King, Ralph Abernathy, Bayard Rustin, Fred Shuttlesworth, C. T. Vivian, and others—but these individuals were supported by countless anonymous volunteers, especially by black women, who constituted the majority of the membership in churches, where so much of the organizing took place. In the truest sense of the word, they were patriots, men and women imagining the truly unimaginable in human history: a world without racial discrimination or the dominance of one group by another. Naturally, this idealism inspired the young. Students volunteered, risking their lives to integrate lunch counters and interstate buses, and founded their own organization, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). At the forefront of the movement, they attended workshops to prepare themselves for nonviolent civil disobedience (fig. 2) and fanned out across the South’s most dangerous segregated counties to register black voters, bringing them the precious franchise promised to every citizen in the Fifteenth Amendment.

Expand image.

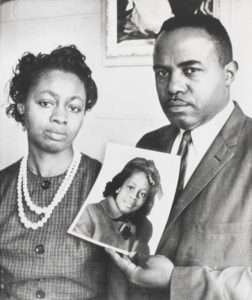

During one Freedom Summer, three young civil rights workers—Michael Schwerner, James Chaney, and Andrew Goodman—were murdered in Mississippi. Four black girls—Addie Mae Collins, Carol Robertson, Cynthia Wesley, and Denise McNair—were killed in the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church Sunday School in Birmingham on September 15, 1963 (fig. 3). Although they were practitioners of nonviolence, civil rights workers and their families were dogged by violence and death. During the tempestuous 1960s, violence and death spread into the political arena, which saw the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy, his brother Robert, the former Nation of Islam leader Malcolm X, King, the Black Panther spokesman Fred Hampton in Chicago, and the murders of far too many others. So relentless was the violence of this period, the “long hot summers” of cities burning, that the federal government prepared itself for the possibility of civil war.

Fortunately, at this pivotal moment in the nation’s history, Americans chose social evolution over racial chaos. They enshrined that decision in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, two monumental acts of legislation that finally made good on the Founders’ “promissory note” that King spoke of so eloquently in his 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered during the March on Washington—a note of liberty “to which every American was to fall heir.”

The civil rights movement is now forty years behind us, but its legacy permeates every fiber of American society. Its impact has rippled far beyond these shores, inspiring freedom fighters in South Africa and those who took to the streets in Czechoslovakia during that country’s “Velvet Revolution.” The movement’s language and strategies were eagerly adopted by women, farm workers, gay Americans, and the elderly and disabled in their struggles for equality, respect, and justice. Like the Revolution and the Civil War, the civil rights movement revitalized and refined the dream of democracy. More than anything else, this watershed moment in history reminds us that we ourselves must shepherd and nurture that dream at the dawn of the twenty-first century.

Citation

Johnson, Charles. “Introduction.” In Road to Freedom: Photographs of the Civil Rights Movement, 1956–1968, edited by Julian Cox, 13–17. Atlanta: High Museum of Art, 2008. https://link.roadtofreedom.high.org/essay/introduction/.