Bearing Witness, Part 4

At Close Range

Bruce Davidson (American, born 1933), Kelly Ingram Park, Birmingham, Alabama (detail), 1963, gelatin silver print, 5 1⁄16 × 7 7⁄16 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from Jess and Sherri Crawford in honor of John Lewis, 2007.263. © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos.

Expand image.

Most photographers would probably acknowledge that being in the right place at the right time trumps all skill for news stories. As the example of photographers as varied in training and background as Ernest C. Withers, Danny Lyon, Horace Cort, and Joe Postiglione has shown, having an instinctive sense of where to stand and when to click the shutter makes all the difference. One of the fascinating aspects of the civil rights movement as a photographic subject is the abundance of significant images that have been made by amateurs, many of whom used their cameras pragmatically—as a tool to record and classify information. A cache of photographs made by a detective in the Birmingham police department, Lonnie J. Wilson, shows a side of that city’s richly documented civil rights history that is not commonly seen.1 One snapshot, made from a vantage point tucked in behind a bevy of firemen (fig. 11), reveals the devastating power of the heavy fire hoses that released enough pressure to skin the bark from a tree at one hundred feet.2 We know that established newsmen and artist photographers such as Charles Moore Plate 31, Plate 32, Bob Adelman Plate 28, and Bruce Davidson Plate 29, Plate 30 were also present that day and well placed to record what happened, but none quite captured the “on top of the action” feeling conveyed by this police photographer, who was shooting from behind the lines.

Expand image.

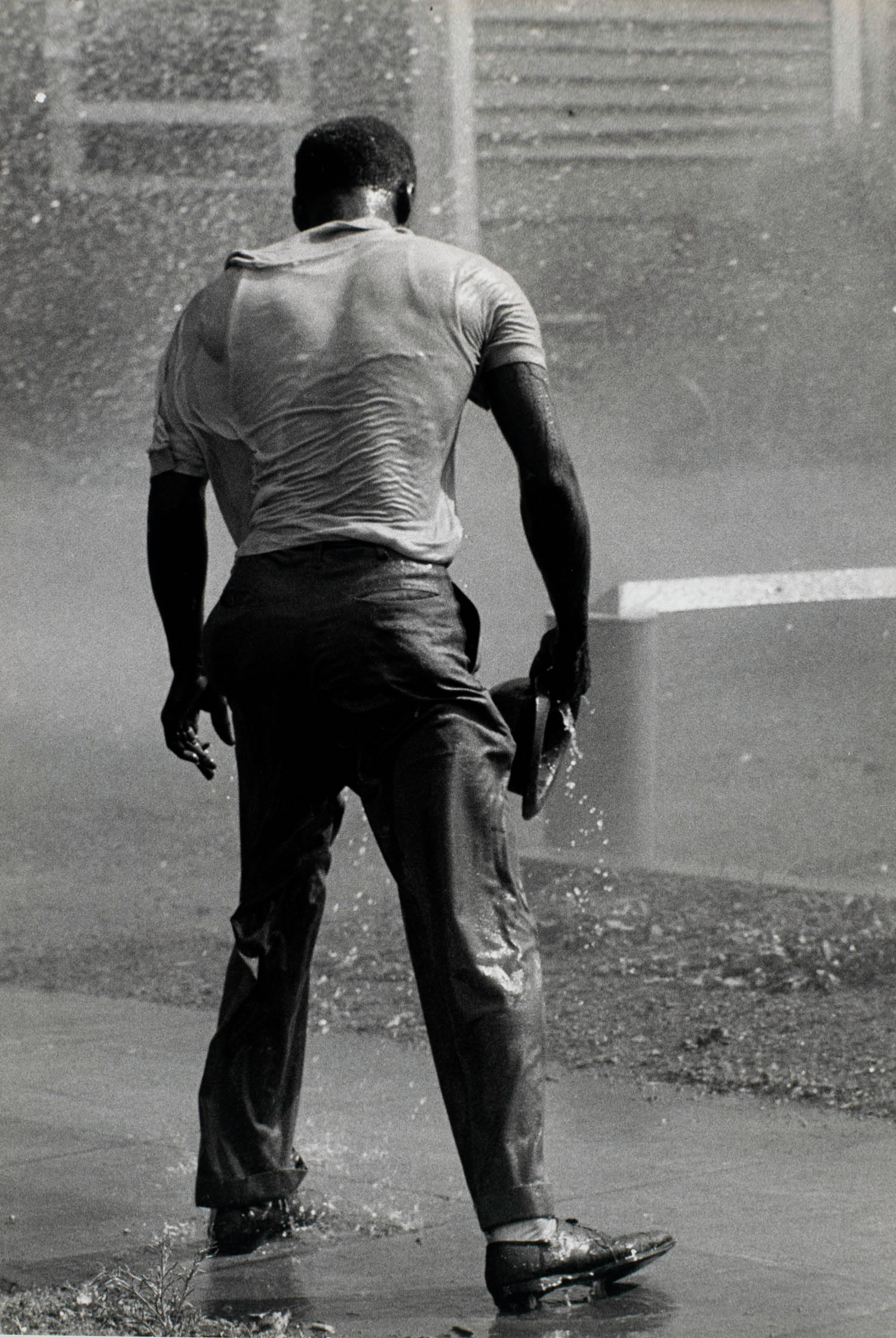

Of the photographers mentioned above, Adelman perhaps comes closest.3 His compelling picture of a lone woman desperately struggling to keep her feet and maintain her dignity while being pummeled by a white laser of water (fig. 12) was made at the edge of Kelly Ingram Park from a protected position between a police officer at left and an unknown spectator at right. Moments later, Charles Moore made several exposures of the same woman, capturing frame by frame her desperate face-off with a batonwielding police officer (fig. 13). Of them all, it was Moore’s hosing photographs that received the most media exposure. They were reproduced in an eleven-page story in Life, where the “slick paper and large format gave the photos a vividness and sense of enormity that newspapers couldn’t touch.”4 It is Moore’s eye for the individual figure that makes his photographs stand out.

Expand image.

In one startling picture in which a woman is shown knocked to the ground by a stinging high-pressure fusillade Plate 32, her purse wrenched from her grasp by the force of the water, the viewer shares the drenched chaos of the scene. Her fingertips alone are keeping her from falling flat, with the unmistakable glint of her wedding ring providing a jarring reminder of the commitment and sacrifice in her action. Collectively, Moore’s photo story met the standards of intensity and personal accountability that one expects of a work of art. Despite its undeniable power and shock value as an ensemble, the best of Moore’s photographs transcend the narrative of which they are a part.

That same day, May 3, 1963, Moore and Bill Hudson, a photographer working for the Associated Press, made some of the most important photographs of the most newsworthy episode in the entire civil rights movement—the dog attacks in Birmingham. Hudson, a former paratrooper, had sufficient experience of police hostility toward photojournalists to keep his camera (most of the time) hidden from view under his jacket, only to be brought out at the optimal moment. Hudson was there to capture the instant when a police officer grabbed the fifteen-year-old Walter Gadsden by the collar, pulling the youth toward him to provide an easy target for the attack dog at his side (fig. 14 and Plate 25). Gadsden looks on, powerless to repel the dog lunging for his abdomen.5 Standing but a few feet from his subject and using a short-range wide-angle 28mm lens, Hudson produced a photograph that brings the viewer into the heart of the action with almost brutal immediacy. The look and smell of the scene are almost palpable. The image hit the AP wire immediately and, in the professional parlance, “took the play,” gaining rapid distribution; the following morning it ran on the front page of both the New York Times and the Washington Post.6 President John F. Kennedy was outraged, and the photographs of Moore and Hudson were in large part the catalysts for swift federal action. These photographs and the media coverage of Birmingham had served their purpose.

Expand image.

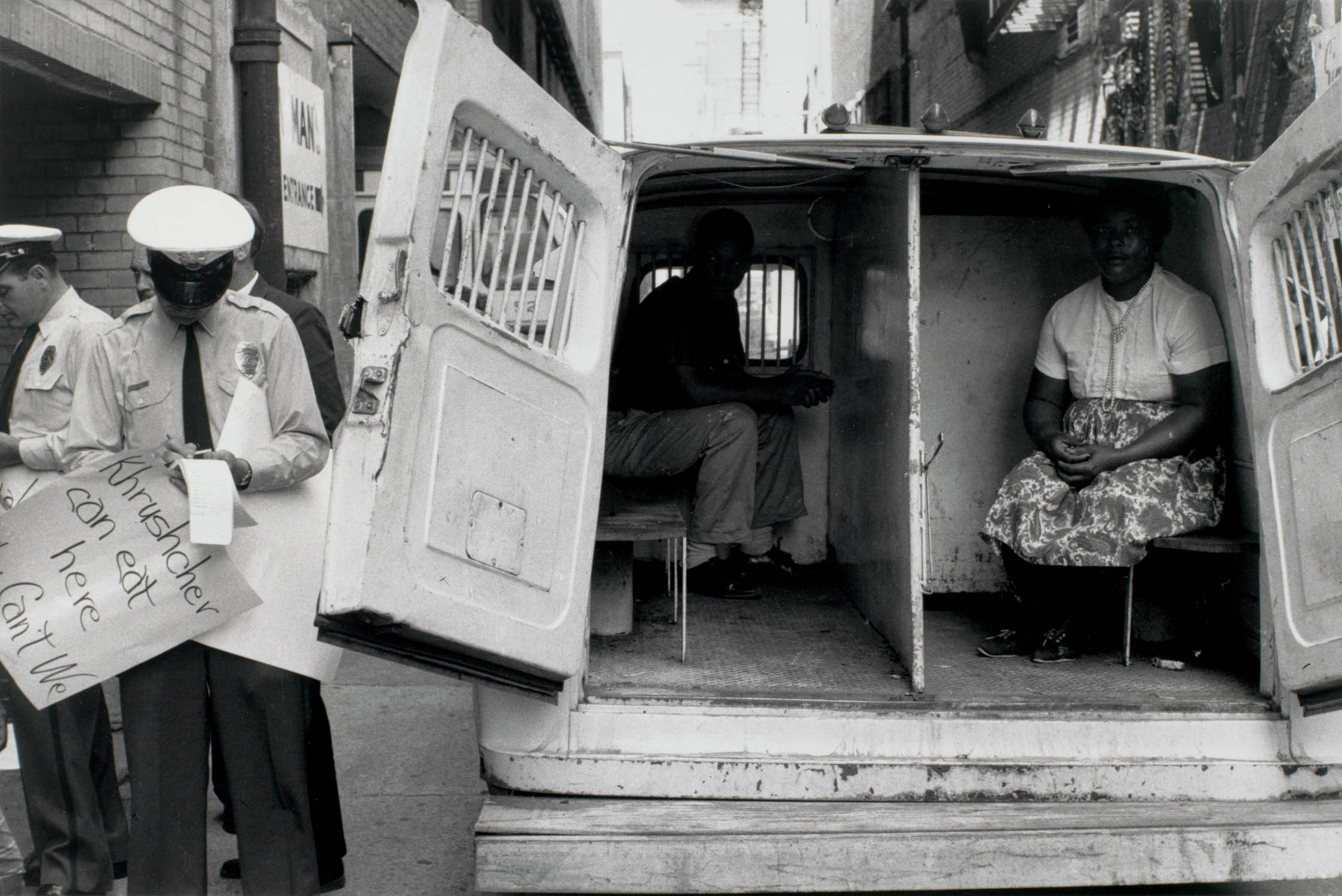

In stark contrast to Hudson and Moore’s inflammatory photographs of the dog attacks are photographs made by Birmingham police detective Lonnie J. Wilson. They show a much more controlled situation on the city’s streets—the calm before the storm. This is the view of the demonstrations that was published in the Birmingham daily newspapers, which portrayed the police and firefighters as models of reserve. Movement historians have explained how carefully coordinated the Birmingham protests were,7 and these photographs reveal the meticulous preparations of the police department to block off major intersections with patrol cars and motorcycles, with plainclothes officers and officials at the ready and, of course, with the canine unit on hand to control the demonstrators (figs. 15 and 16). Such photographs remain largely unpublished, either buried in police files and state archives or maintained relatively untouched in private collections.

The lead organizers of the Birmingham movement alongside Dr. King, men such as Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth and Rev. C. T. Vivian, were alert to the role that the media could play in promoting their position, and they strategically staged conflicts to draw publicity to their cause. By leading scores of well-dressed, committed, and hopeful young blacks into the streets to peacefully protest the segregation of public accommodations, where they were to be met by the defiant public safety commissioner, Eugene “Bull” Connor, only one result was likely. The leaders were able to provide undeniable evidence of the system’s brutality and inequity. It was these young, proud, fearless faces—writ large in black-and-white photographic images—that transformed Dr. King’s campaign and made him and his cause unstoppable.

The violence of the South had reached into me

deeper than my personal pain.—Bruce Davidson8

Expand image.

Expand image.

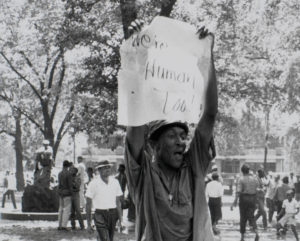

Bruce Davidson’s photographs of the civil rights movement reveal his gift for capturing the closest thing attainable to the actual event while simultaneously conjuring up the feelings associated with it. Historian Deborah Willis praises these photographs for their “layering of meaning,” and their capacity to provide the viewer with a potent and nuanced view of the subject.9 Throughout his career, Davidson has excelled in the art of photographing public moments or subjects from an intimate perspective. He works in a personal way and has stated: “I felt the need to belong when I took pictures—to discover something inside myself while making an emotional connection to my subjects.”10 While his photographs of the Birmingham water hosings Plate 29, Plate 30 have much of the immediacy and directness of other photographs made that day, his emphasis on the desperate attempt of these youths to continue to brandish their handwritten placards in the face of the brutal onslaught adds a distinct layer of emotional power to these pictures (fig. 17 and Plate 29). Davidson is attuned to his surroundings and seems to know how and when to collaborate with the ephemeral flow of the situation in which he finds himself. His goal is always to show what the environment feels like, to demonstrate that the medium of photography can communicate emotions. As he has stated, “I’m not trying to tell a story as such, but to work around a subject intuitively, exploring different vantage points, looking for its emotional truth. If I’m looking for a story at all it’s in my relationship to the subject.”11

Expand image.

Davidson’s approach owes much to the philosophy of Henri Cartier-Bresson, whose work he studied under Ralph Hattersley at the Rochester Institute of Technology. It was Cartier-Bresson’s seminal book The Decisive Moment (1952), which included some one hundred photographs and an accompanying text by the photographer, that transformed Davidson’s thinking about himself in relation to the medium. For Cartier-Bresson the decisive moment signified that instant when the photographer “finds” himself in a picture. He said: “The discovery of oneself is made concurrently with the discovery of the world around us, but which can also be affected by us. A balance must be established between these two worlds—the one inside us and the one outside us. As a result of a constant reciprocal process, both these worlds come together to form a single one.”12 For his part, Davidson seems to understand that, despite frequent claims to the contrary, photography has never been a medium especially suited to storytelling. Isolating single fragments out of the continuity of time—which is what photographs do—is counter to the idea of narrative. Davidson’s photographs, at their best, subvert the narrative idea and instead describe the look and feel of an experience, memorializing the quality of a particular moment Plate 18, Plate 24, Plate 29, Plate 30.

Citation

Cox, Julian. “Bearing Witness: Photography and the Civil Rights Movement.” In Road to Freedom: Photographs of the Civil Rights Movement, 1956–1968, edited by Julian Cox, 19–47. Atlanta: High Museum of Art, 2008. https://link.roadtofreedom.high.org/essay/bearing-witness-part-4-at-close-range/.