Bearing Witness, Part 3

The Student Movement

Danny Lyon (American, born 1942), SNCC Office Staff, Atlanta, Georgia (detail), 1963, gelatin silver print, 6 1/4 × 9 1/2 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from Jess and Sherri Crawford in memory of Paul Robeson, 2007.207. © Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos, courtesy of Edwynn Houk Gallery.

Get out the lunch-box of your dreams.

Bite into the sandwich of your heart,

And ride the Jim Crow car until it screams

Then—like an atom bomb—it bursts apart.—Langston Hughes1

In its earliest days, the sit-in movement was a spontaneous student-led enterprise that quickly became a particularly effective form of nonviolent direct action. As an indication of a new and burgeoning activism on the part of young blacks, it was a strong example of their genuine willingness to turn to unfamiliar and untried ways to express their grievances and to seek redress. While this form of peaceful protest began in Greensboro, North Carolina, in the winter of 1960, within six months cities throughout the South were participating. Nashville became a particularly prominent center, led by a triumvirate of ministers—C. T. Vivian, James Lawson, and Kelly Miller Smith—vanguard strategists in nonviolent direct action, who counseled and prepared a core of educated and motivated young students who proved ready to go to jail for their beliefs. Rev. Lawson was particularly influential, having trained in India and learned the validity of Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence as an instrument of social change.2 Lawson traveled to campuses throughout the South, leading workshops for students black and white. His most basic teaching was this: “Ordinary people who acted on their conscience and took terrible risks were no longer ordinary people. They were by their very actions transformed. They would be heroes, men and women who had been abused and arrested for seeking the most elemental of human rights.”3 The students were taught how to use the tactics of passive resistance and how to respond to verbal and physical abuse (see Introduction, fig. 2). Some were among the first members of their families to go to college, and they reveled in the freedom to work out a new approach to counteracting discrimination and prejudice. Among them were Diane Nash, James Bevel, and John Lewis, all of whom started “feeling the power of an idea whose time had come”4 and who went on to become important leaders who had a major impact on the course of the nonviolent movement.

Howard Zinn, a historian who was also active in the movement, writing in 1964 described the impact of the photographic image on the cause of student protest: “Their task is made easier by modern mass communication, for the nation, indeed the whole world, can see them on the television screen or in newspaper photos—marching, praying, singing, demonstrating their message.”5 The principal civil rights organizations—Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, commonly pronounced “snick”)—were adept at employing the media to advance their goals, though each group independently believed that the photographs made by newspaper photographers and “outsiders” could not be relied upon to promote their causes and help raise funds to support their mission.

Of all the movement organizations, SNCC was the boldest and most progressive in its approach to media outreach, despite the fact that its membership comprised almost exclusively young, relatively inexperienced students. Its executive director, James Forman, was savvy about publicity and had the foresight in the spring of 1962 to appoint Julian Bond (at that time an undergraduate at Morehouse College and a participant in the vigorous student-led sit-in movement in Atlanta) as SNCC’s director of communications. Bond inaugurated The Student Voice, a newsletter that ran detailed reports on movement events, many illustrated with photographs. He was responsible for formalizing SNCC’s press procedures, which included the issue of a twelve-point internal memo on the subject for its members: “It is absolutely necessary that the Atlanta office know at all times what is happening in your particular area. When action starts, the Atlanta office must be informed regularly by telephone or air mail special delivery letter so that we can issue the proper information for the press. (Atlanta has the two largest dailies in the South; we have contacts with the New York Times, Newsweek, UPI, and AP, the two wire services; we have a press list of 350 newspapers, both national and international).”6 The same memo includes specific instructions for photographs: “Please delegate one or two people to take photographs of the action. If you have facilities to develop films immediately where you are, have the pictures developed and send the shots to us. If there are no facilities, send the roll(s) of film to us in manila envelopes air mail special delivery addressed personally to James Forman or Julian Bond, along with descriptions of what the photographs are about.”7

Expand image.

Bond and Forman recognized that photographs, used appropriately, could be instrumental to their fundraising efforts. They also understood that the medium could be used for political gain, providing pictures for press releases and illustrations for brochures and posters (fig. 7). Photography could serve as the primary tool for documenting the movement.8 It was Forman who recruited Danny Lyon to be SNCC’s first official photographer based out of their Atlanta headquarters. Lyon, a native of New York, was just twenty years old and an undergraduate at the University of Chicago when he began working with the organization.9 He made an immediate impact, bringing raw talent and a sense of adventure to the enterprise. In his work for SNCC he was not tied to traditional newspaper deadlines, or to any specific editorial brief, but had autonomy to choose whom and how to photograph. He was free to explore events on the ground in his own distinctive way while simultaneously absorbing the culture of the organization. He learned as he went, initially by establishing a strong rapport with Forman, for whom he served as a driver, ferrying him back and forth from meetings and demonstrations.10 He gained Forman’s trust and that of his principal colleagues, including Bond and John Lewis. Lyon became a valuable asset for SNCC and was deployed wherever his skills could be put to good use. Within this loosely structured arrangement he remained keenly aware of his role in the service of SNCC’s goals: “To the watching world, SNCC was faceless. . . . My photographs were used to help create a public image.”11

Lyon’s photographs captured the day-to-day grind of marches Plate 19 and meetings Plate 20 as well as the frenetic, highly charged atmosphere of demonstrations and altercations that went right to the heart of the subject. In June 1963 he was dispatched to the textile town of Danville, Virginia, where police had attacked (with billy clubs and dogs) demonstrators praying at city hall. Lyon recalled that “forty-eight out of sixty-five demonstrators were injured,” some severely.12 It was the first time he had experienced the grim reality of segregated hospitals. Among the injured was Dottie Miller, a young woman who was coordinating SNCC’s efforts in Danville. Lyon set to work photographing the wounded as well as the demonstrations and mass meetings that immediately followed. Within a few weeks, he and Miller had created a ten-page pamphlet documenting the violence in Danville. Miller wrote the text and Lyon provided the photographs and designed the layout. The back page of the pamphlet provides a clear statement of SNCC’s mission as well as the function of such a document:

THE STUDENT NONVIOLENT COORDINATING COMMITTEE grew out of the student sit-in movement in 1960. It is composed of local protest groups across the South, a staff of 190 people, and friends of SNCC groups in the North.

SNCC staff and local affiliate group members work on voter registration and direct action in the hard core areas of the South. They daily face the violence portrayed in this pamphlet.

SNCC looks towards a day when all men shall walk with their heads high, each with equal opportunities, unafraid.

The costs of this pamphlet have been borne by SNCC in order that the Danville story could be told. Your contribution will help cover printing costs and further the struggle for human dignity in the South. Make checks payable to SNCC.13

Expand image.

Despite the hardships of a life on the road, flitting from place to place, sleeping in cars and on floors in safe houses, and putting himself in highly volatile situations, Lyon admitted: “The Danville pamphlet, a poster that makes money for SNCC, even selling pictures and passing the check on to SNCC; these things have, for a brief moment, given me a satisfaction previously unknown.”14 Lyon’s work for SNCC was very effective. In the summer of 1963, a few weeks after his stint in Danville, Lyon managed to sneak up to a makeshift jail in rural southwest Georgia and take pictures of a group of teenage girls who had been arrested for demonstrating in the streets of Americus.15 The girls were held incommunicado (some for more than a month) without charges filed against them, in a stockade several miles away from town in cramped, filthy conditions. At great personal risk, Lyon sneaked around the building, photographing the girls through the bars from outside and documenting the atrocious conditions in which they were being held—a single toilet and a dripping shower head as the only source of water. Lyon’s photographs of the stockade (fig. 8) were later entered into the Congressional Record, providing evidence that was instrumental to securing the girls’ release.

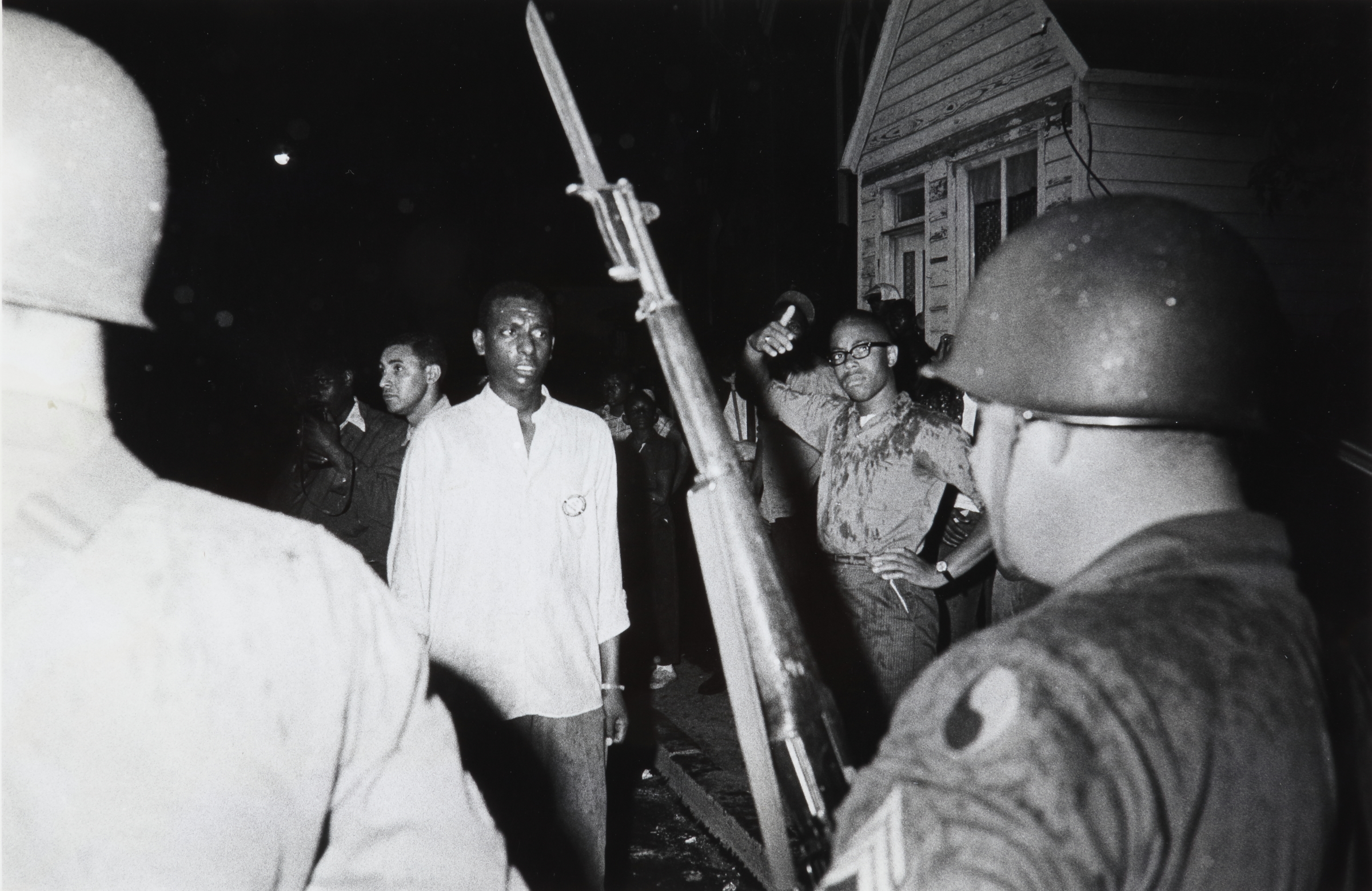

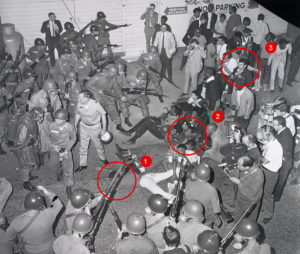

Another of Lyon’s important missions for SNCC took him to Cambridge, Maryland, in the spring of 1964. There he made a shocking picture of fellow SNCC photographer Clifford Vaughs being violently apprehended by the National Guard Plate 39.16 Vaughs, who worked for SNCC primarily in Virginia and Maryland, looks as if he is being pulled limb from limb, with at least three guardsmen clutching at his clothes and legs, and a student protestor in the foreground holding onto his right ankle in a vain attempt to resist the arrest. At right foreground stands an officer, clearly of senior rank, hat in hand, staring grimly at the camera. Importantly, Lyon recollects that he made the photograph using a flash unit provided by Vaughs, who told him that he would not need it because he planned on being arrested that night.17 Vaughs realized the publicity value of a photograph of his arrest, which could be charged with political and racial implications. His richly compelling, highly tactical form of direct action reveals the nuanced choreography underlying events that appear to be spontaneous in the photographs that record them.

Expand image.

A news photographer in attendance at the same episode (fig. 9) captured the unfolding action from the rooftop of the building that is pictured in the rear of Lyon’s photograph. From his elevated position, George Cook, working for the Baltimore Sun, captured a battalion of bayonet-wielding National Guardsmen swarming around Clifford Vaughs (1), the nearby Stokely Carmichael (2), and the watching Lyon (3), standing just a few feet away from the main action. Despite his physical proximity, Lyon seems to retain a measure of emotional distance from what is taking place, which is part of what allowed him to produce his own remarkable picture of the incident. He does not have the camera held up to his eye; rather, he seems to be intently watching the event play out in front of him. The uncanny brilliance of Lyon’s photograph, which frames the action so intensely, is that it provides the viewer with the vicarious sense of what it was like to be there. He is able to convince us that he is the only photographer present, while Cook’s picture establishes that this was far from the case. Besides Lyon, there are no fewer than five still photographers and two film cameramen caught in the frame.

Earlier the same night, Lyon made a striking photograph of Stokely Carmichael Plate 40 before the young activist was felled by a particularly severe tear-gas attack. Over the course of two days and nights Lyon shot five rolls of film, intent on providing a detailed photographic record of what was happening.18 It was difficult and dangerous work, nighttime demonstrations being especially unpredictable. As Lyon recalled: “I’ve never much cared for the dark, didn’t own a flash, and would take pictures at night by leaning on a wall and making time exposures or by just shooting when a TV cameraman turned on his lights.”19 He adapted to the circumstances, knowing that he was there to do a job, which was to record and observe rather than to participate in the direct action. This subtle but important distinction is what distinguishes Lyon’s photographs, which are at the same time persuasively objective and emotionally charged.20

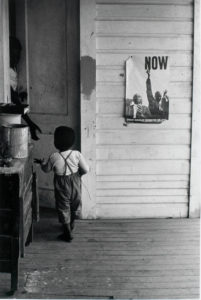

By 1964 a separate department within SNCC—SNCC Photo—was established. SNCC Photo enlisted and trained more than a dozen photographers to actively record and document the movement. They included Tamio Wakayama, Clifford Vaughs, Joffre Clark, Rufus Hinton, Bob Fletcher (see fig. 7), Julius Lester, and Maria Varela, among others. Besides setting up darkrooms, collecting supplies, and providing publicity and documentation about the movement, SNCC Photo published pamphlets, posters, and the 1964 book The Movement.21 That same year, with the support of SNCC, Matt Herron established the Southern Documentary Project to cover activities in the South during “Freedom Summer.” The project, based in Mississippi, was a statewide effort to help register voters, run “Freedom Schools,” set up community centers, and document areas of need and racial injustice throughout the state. Dorothea Lange served as SNCC’s advisor on the project, an indication of the organization’s intent to model its work on the tradition of the FSA photography of the Depression era: “SNCC Photo also documents the rural life of the South in a continuation of the work begun by Walker Evans and others under the Farm Security Administration program in the 1930s.”22

Expand image.

Freedom Summer was a wide-ranging operation in which the primary civil rights organizations—SNCC, CORE, SCLC, and the NAACP—came together to form an umbrella group called the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), with offices in Columbus, Greenwood, Clarksdale, Meridian, and Hattiesburg, staffed mostly by college students who fanned out across the state in the summer of 1964. Freedom Summer got off to a horrific start with the kidnapping and disappearance of Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner on June 21, 1964, in Philadelphia, Mississippi.23 Goodman and Schwerner were white and from the North; Chaney was black and a native of Meridian. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy sent the FBI and scores of federal marshals to investigate. Though the vehicle the three civil rights workers were driving was dredged from the bayou within a few days Plate 41, it was more than a month before their bodies were found, buried in an earthen dam on the property of a noted local Klansman, Olen Burrage.24 The FBI was led to the exact location by an informant, lured by a reward of $30,000. Life magazine sent photographer Bill Eppridge (and reporter Mike Murphy) to Philadelphia soon after the news broke. State authorities would not allow the two men anywhere near the crime scene, so Eppridge rented a plane to fly over the site and made aerial photographs (fig. 10). Everywhere they went, Eppridge and Murphy were followed by members of the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission, an agency created by the state legislature in 1957 to resist federal rights legislation. They established contact with the Chaney family and asked their permission to photograph the funeral and burial of their son. James Chaney was the eldest of five children, with three sisters and one brother. It was Ben Chaney, ten years old at the time, who took his brother’s death the hardest. In one photograph Plate 42 from an extensive series,25 Eppridge eloquently captures the devastating grief and sorrow wrought on the family, as well as the lingering anger and resentment that were felt most keenly by this young boy who had lost his only brother.26

Citation

Cox, Julian. “Bearing Witness: Photography and the Civil Rights Movement.” In Road to Freedom: Photographs of the Civil Rights Movement, 1956–1968, edited by Julian Cox, 19–47. Atlanta: High Museum of Art, 2008. https://link.roadtofreedom.high.org/essay/bearing-witness-part-3-the-student-movement/.