Bearing Witness, Part 1

Photography and the Civil Rights Movement

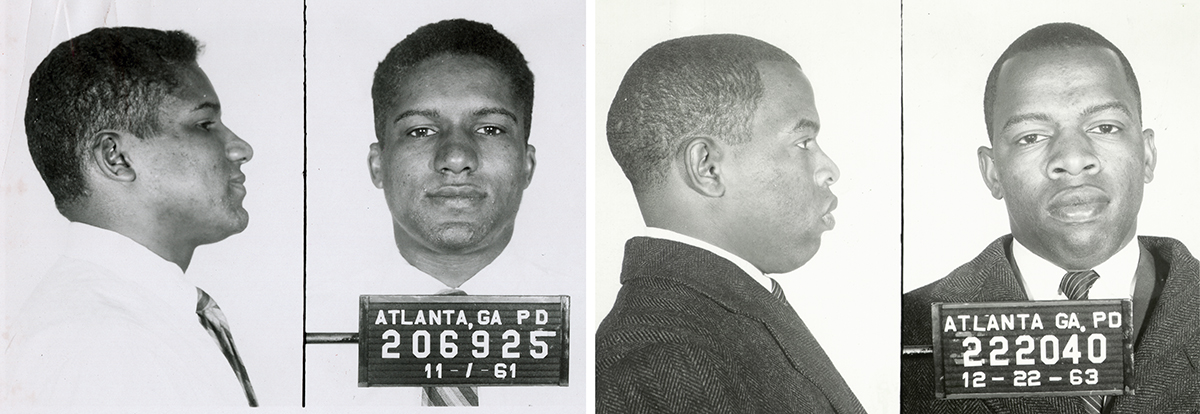

Unknown photographer, James Forman and John Lewis—Police Mugshots, gelatin silver prints, 3 3/4 x 5 1/16 inches, collection of Emory University, Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library.

By Julian Cox

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?Maybe it just sags

Like a heavy load.Or does it explode?

—Langston Hughes 1

The civil rights movement and direct action social protest took many forms in the 1950s and 1960s: protest marches, nose-to-nose showdowns between demonstrators who offered no resistance and city police, national guardsmen, state troopers, and sheriff’s deputies wielding billy clubs, cattle prods, tear gas, fire hoses, and dogs in response. It also involved court fights against segregation in schools and libraries and on buses and trains, and opposition to segregation at drinking fountains, in restrooms, and in voting booths. It sparked sit-ins at lunch counters, boycotts, and “freedom rides” on buses traveling from the North to the South. Asserting civil rights became a cause, a social revolution unlike anything the country had experienced since the Civil War. It involved thousands of acts of individual courage undertaken in the pursuit of freedom. While nonviolent protest was the dominant tactic, shock waves of violence broke out across the nation, with civil disturbances erupting in Detroit, Chicago, Newark, and Los Angeles. For the media and for photographers, it was an engaging, demanding, and sometimes highly dangerous story.

Consequential images of the civil rights movement were made by an array of photographers—artists, photojournalists, movement photographers, and amateurs—each with a distinct point of view. While their individual approaches may have differed, they all seem to have shared an awareness of the historical significance of the moment, and understood that they were documenting a nation in tumult and transition. As Steven Kasher has put it, “The great photographs of the movement were crafted with urgent passion—for their own time and for the future.”2 Typically, the photographs they produced are valued as historical evidence and for their capacity to effect cultural and political change. That is, their function as social documents is commonly emphasized above their status as critical or aesthetic representations. But occasionally, and profoundly, they show us something that we have not seen before—a point of view that prompts us to look at the world, and the subject, with renewed concentration. The images present the full range of poverty, brutality, and outright hatred, but also glimpses of hope, unity, and a collective determination to stand up and move forward in the face of seemingly impenetrable obstacles.

Photojournalists were trained to record newsworthy events according to the “professional principle of objectivity,”3 even if that meant putting themselves in danger in order to get the picture. Black photographers—and reporters—often worked under volatile and perilous conditions Plate 6. Moses Newson, who covered the civil rights beat for the Tri-State Defender in Memphis and later for the Baltimore Afro-American, was brutally attacked while reporting on the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957, and again during the Freedom Rides in 1961.4 Charles Moore, who was a staff photographer for the Montgomery Advertiser in the early 1960s (and who also supplied images to publications such as Life magazine), remembers that it was the simple realization of knowing and believing in the difference between right and wrong that compelled him to make his work. Feelings of fear and vulnerability hardly entered his mind—he was too committed to telling the story to allow concern for his personal safety to interfere with his mission.5

Expand Image.

More than any other medium, photography promises an unhindered immediacy of representation. It readily obeys the rules of nonfiction. Its job is to make the world visible, which it does more democratically than all other visual arts. Sometimes the most artless, undemonstrative pictures can reveal the most about a subject. A photograph of six half-empty beer bottles, stuffed at the neck with rags, neatly arranged in a row on a table (fig. 1) raises questions: Who made this and why? For whom was it produced? How does it relate to the ostensible subject under discussion—civil rights photography? This snapshot is stamped and dated on the verso “Lonnie J. Wilson / 1967,” and was made by a lifetime detective who worked for the Birmingham, Alabama, police department.6 It is a piece of evidence, a testimony, and an exemplar of photography as a stop-time device—qualities that make every photograph, whether sophisticated or humdrum, unique. Police mug shots (see banner image above) share similar qualities. Great snapshots such as these may be among the highest forms of photography because they are so ripe with suggestion. We know that they come with a story. They tell us something significant about the human condition. Their wonder is that they conjure in plain, pithy visual language the same kind of imaginative voyaging that is active in the eloquent verse of Langston Hughes.

Citation

Cox, Julian. “Bearing Witness: Photography and the Civil Rights Movement.” In Road to Freedom: Photographs of the Civil Rights Movement, 1956–1968, edited by Julian Cox, 19–47. Atlanta: High Museum of Art, 2008. https://link.roadtofreedom.high.org/essay/bearing-witness-part-1-photography-and-the-civil-rights-movement/.