Afterword

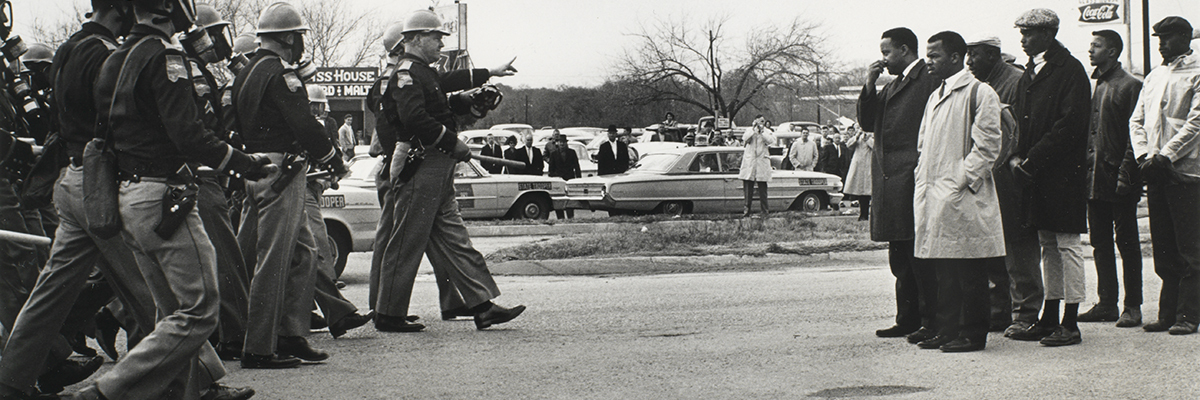

James “Spider” Martin (American, 1939–2003), State Trooper Gives Marchers “Two Minute Warning,” Selma, Alabama (detail), 1965, gelatin silver print, 6 × 9 1/16 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from Kristie and Charles Abney, 2007.215. © 1965 The Spider Martin Civil Rights Collection, all rights reserved, used with permission.

By John Lewis

These powerful images are not make-believe. They are real portraits of American history just the way it happened not too long ago in the Deep South. These pictures are an outgrowth of the struggles, the suffering, and the strains of humanity yearning to throw off the yoke of oppression. They are a testament to the ability of a committed, determined people to transform a nation, even the most powerful nation on earth, and bring it more in line with the call for justice.

If you could not join the sit-ins, the Freedom Rides, or the marches; if you were not born at a time when you could attend the nonviolence training or the community organizing meetings, then there is no better way for you to learn what the civil rights movement was all about than to look into the faces of humanity captured in these photographs.

It took nothing short of raw courage for participants in the movement to stand up to the governor, to the citizens’ council, to mounted police, tear gas, fire hoses, and attack dogs. It was dangerous—very dangerous—for anyone to say no to segregation and racial discrimination simply by taking a seat at an integrated lunch counter or on a public bus. It was almost like committing suicide for an African American to go to the courthouse in the Delta of Mississippi or the Black Belt of Alabama and declare his or her intention to register to vote. White organizers were risking their lives trying to register black Americans to vote. The cameras of reporters, their pads and pens, were seen by segregationists as an invitation to brutality.

Our homes were bombed and our jobs were threatened. Some of us were expelled from college or run out of town. Peaceful, nonviolent protesters were trampled by horses, struck with bull whips, beaten with nightsticks, arrested, and taken to jail. Some were shot and even killed, but we buried our dead and kept on coming. We knew we would not stop; we would never turn back until we tore down the walls of legalized segregation.

We didn’t have a cell phone. We didn’t have a website. We didn’t have a computer or even a fax machine, but we used what we had. We had ourselves, so we put our bodies on the line to make a difference in our society. We were just ordinary people with an extraordinary vision, imbued with the discipline and philosophy of nonviolence. We were convinced that if we adhered to the way of nonviolence as taught by Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi, we could produce an all-inclusive world society—a Beloved Community—based on simple justice that values the dignity and the worth of every human being.

Central to our philosophic concept of the Beloved Community was an affirmation of faith in humanity—the willingness to believe that man has the moral capacity to care for his fellow man. When we suffered violence and abuse, our concern was not for retaliation. We sought to understand the human condition of our attackers and to accept the suffering in the right spirit. We believed that ends and means were inseparable, so if we wanted to create a peaceful society, then we had to use the methods of peace and goodwill. Our protests were love in action. We were attempting to redeem not only our attackers, but the very soul of America.

Perhaps the greatest and most timeless gift of this history is that it serves as a reminder that you can make a difference. No matter how fierce your adversary, no matter how organized the opposition, no matter how powerful the resistance, nothing can stop the movement of a disciplined, determined people. These images make it plain that we are standing on the shoulders of the martyrs of the civil rights movement.

We must never forget that men and women gave their lives for our democracy. Some of them are the martyrs we knew—Martin Luther King Jr., Andrew Goodman, Mickey Schwerner, James Chaney, Viola Liuzzo, Jimmie Lee Jackson—others are countless and nameless. But they gave their lives so that we might live in a better nation today. Through these photographs we can see their pain, their struggle, and their sacrifice. They have informed us with their testimony of faith, and they leave us with a legacy, a mission, and a mandate. We must do our part to make sure that these men, women, and children did not live and die in vain.

We are fortunate in our society that a means of resistance has been built into the law and the political process—the vote. The vote is the most powerful nonviolent tool we have in a democracy. We must use our votes, our power, and our organizational abilities to create a movement for good. We must not give up this power. We must not give in. We must not give out. We must use what we have—all of our talents, resources, energy, and creativity. We must do all we can to help build a better nation and a better world.

In the 1960s, this nation witnessed a nonviolent revolution under the rule of law, a revolution of values, a revolution of ideas. We have come a great distance in just a few decades, but we still have a distance to go before we build the Beloved Community. There is still a need to change the social, political, economic, and religious structures around us. There is still a need for a revolution of values and ideas in this nation and throughout the world. There is still a need to build a Beloved Community, a nation and a world at peace with itself.

Citation

Lewis, John. “Afterword.” In Road to Freedom: Photographs of the Civil Rights Movement, 1956–1968, edited by Julian Cox, 146–147. Atlanta: High Museum of Art, 2008. https://link.roadtofreedom.high.org/essay/afterword/.