Bearing Witness, Part 5

Foot Soldiers

Matt Herron (American, 1931–2020), Selma to Montgomery March, Alabama (detail), 1965, gelatin silver print, 5 1/4 × 9 11⁄16 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from Jess and Sherri Crawford in honor of John Lewis, 2007.244. © Matt Herron/Take Stock, courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery.

The elevation of Dr. King to iconic status as a civil rights leader has partially obscured the courageous and determined efforts of thousands of ordinary people who participated in and contributed to the movement. Gifted and dedicated local organizers throughout the South were the backbone of the movement, and they made it possible for Dr. King and other leaders to transform what was considered a local issue into a national crisis that merited international attention.1 While the movement’s formal leadership may have come from businesses, churches, and national organizations, it was mostly private citizens—many of them women—who played prominent roles in organizing effectively for change. One such important grassroots leader was Septima Clark, who taught for forty years in the South Carolina school system before she was summarily dismissed in 1956 for refusing to relinquish her NAACP membership. Clark successfully campaigned to allow African Americans to teach in Charleston and earn pay equivalent to their white counterparts. In the 1950s she regularly taught workshops at the Highlander Folk School on the tactics required to advance school desegregation, voter registration, and leadership in education.2 In 1961 she was recruited by Dr. King and the SCLC to serve as director of education and teaching, a role that required her to carry out citizenship training, voter registration, and literacy programs.

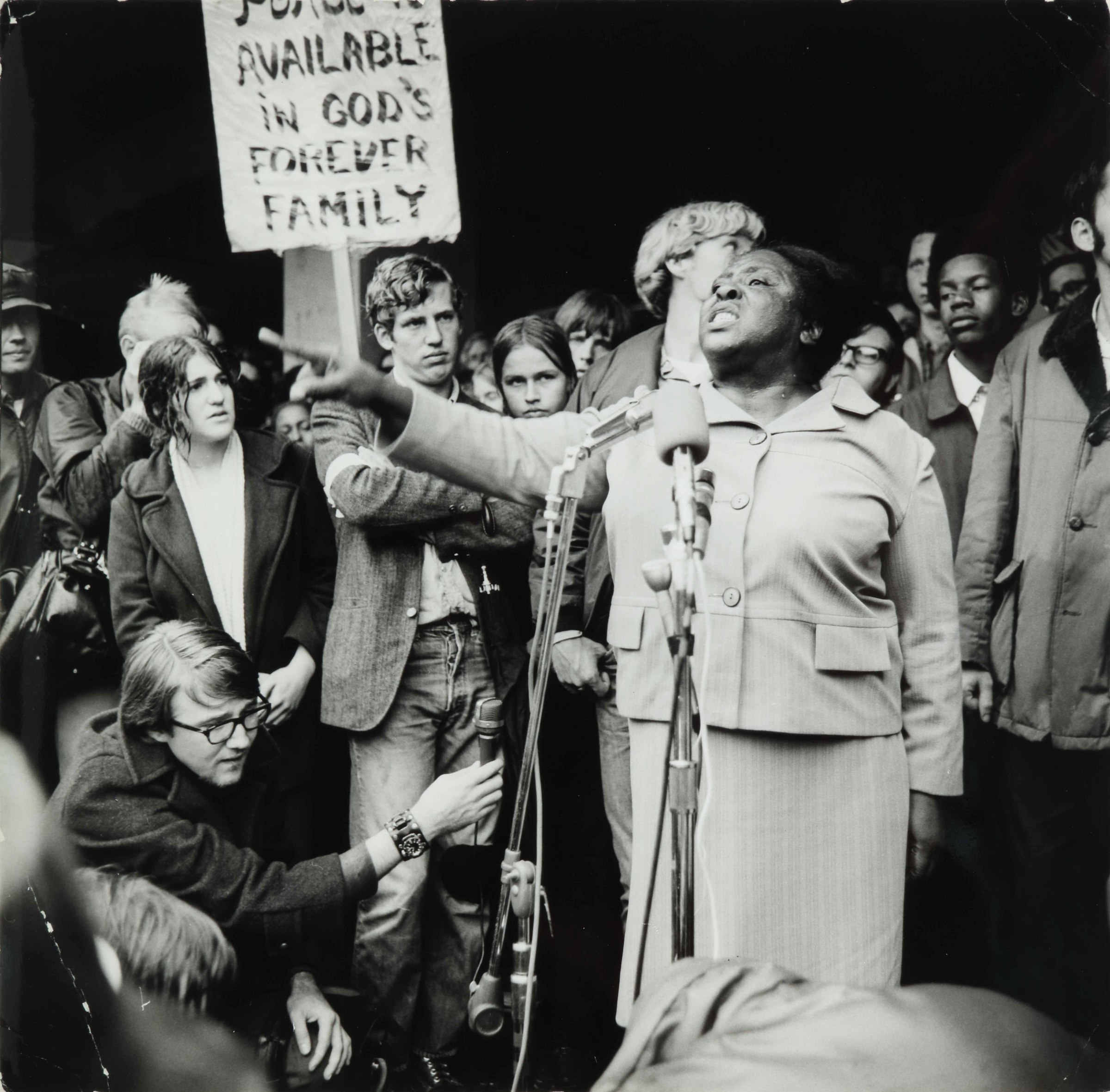

Similarly influential was Fannie Lou Hamer Plate 52, Plate 53, the twentieth child born to a family of sharecroppers in Montgomery County in the heart of the Mississippi Delta. She knew firsthand the impoverished conditions of blacks in the South, and it was her strong desire to improve those conditions that fueled her activism. She worked with SNCC, predominantly in her home state, dedicating herself to voter registration. When she tried to register to vote, she lost her job as a plantation worker and was brutally beaten and arrested on several occasions. The spirit of Hamer’s radical voice is captured in her autobiography, To Praise Our Bridges, which was published by SNCC: “What I really feel is necessary is that the black people in this country will have to upset the applecart. We can no longer ignore the fact that America is NOT the ‘. . . land of the free and the home of the brave.’ I used to question this for years—what did our kids actually fight for? They would go in the service and go through all of that and come right out and be drowned in the river in Mississippi.”3 It was Hamer’s emotional testimony before the Credentials Committee of the 1964 Democratic National Convention that helped bring the crimes inflicted on blacks seeking the right to vote in her home state to a national audience.4

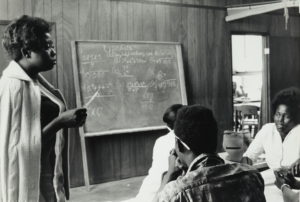

The examples of Clark and Hamer greatly inspired another young educator and activist, Doris Derby, who studied anthropology at the University of Illinois and sought to establish vibrant local organizations capable of responding to conditions in the rural South. A native of New York, Derby became involved in civil rights action in the summer of 1962, when she traveled to Albany, Georgia, to visit a friend who had been arrested there for demonstrating.5 After spending the summer going back and forth between Albany and Atlanta, during which time she worked with James Forman, Septima Clark, and Dr. King, Derby returned to New York and became a founding member of SNCC’s office there. She proved able and resourceful. Derby staged several fundraising events that brought much-needed dollars to the organization. For one such effort she invited Bob Moses, the de facto leader of SNCC’s efforts in Mississippi. Moses suggested that Derby move south to help implement an experimental adult literacy program, which she did at Tougaloo College. She developed instructional materials and methods to prepare black men and women to take the literacy test required to gain voting rights.

Having studied painting as an undergraduate, Doris Derby had a background in the visual arts and firmly believed in the power of creative endeavors to raise the consciousness of black people, in both education and employment. She attended the first meeting of the Poor People’s Corporation at Tougaloo College on August 29, 1965, the main purpose of which was to assist low-income groups in their efforts to initiate and sustain self-help projects of a cooperative nature. These projects were designed to ameliorate the effects of poverty. Derby was also intimately involved with an offshoot agency of the Poor People’s Corporation called Southern Media, Inc., based in Jackson, Mississippi. Its staff coached media and communication skills to black community groups—which included training in the use of still and movie cameras—with the goal of enabling those living in isolated rural areas to document their own lives and communities.6 It was in this environment that Derby first practiced and taught photography.

Expand image.

Derby was largely self-taught in the medium and used her camera primarily to document the role of women in the movement such as L. C. Dorsey, who worked with the Southern Coalition on Jails and Prisons and the Mississippi Council on Human Relations.7 Dorsey founded the North Bolivar County Farm Cooperative Plate 57 to encourage subsistence farming and vocational training for women who had been dismissed from their jobs (mostly as maids and housekeepers in white homes) because they registered to vote. Derby’s study of a volunteer math teacher in Mound Bayou, Mississippi (fig. 18), is typical of the kind of picture she made, melding her passion for community activism with a desire to record a social fabric that was largely ignored by the mainstream media.

Morton Broffman, a passionate and skilled amateur photographer, gave up his profession as a teacher in the mid-1950s to pursue a career as a freelance photographer.8 He worked for Senator Hubert Humphrey in 1960 and served as a presidential campaign photographer for Eugene McCarthy in 1968.9 A committed Democrat and liberal who naturally gravitated toward social causes, Broffman dedicated himself to documenting with his camera some of the key events and gatherings of the civil rights era. For thirty years he was the staff photographer of the National Cathedral in Washington, and in that capacity he photographed many politicians and public figures as well as demonstrations and marches in the nation’s capital.10 He was one of scores of photographers from around the country who traveled to Alabama to participate in and record the Selma to Montgomery March for Voting Rights in the spring of 1965.

Expand image.

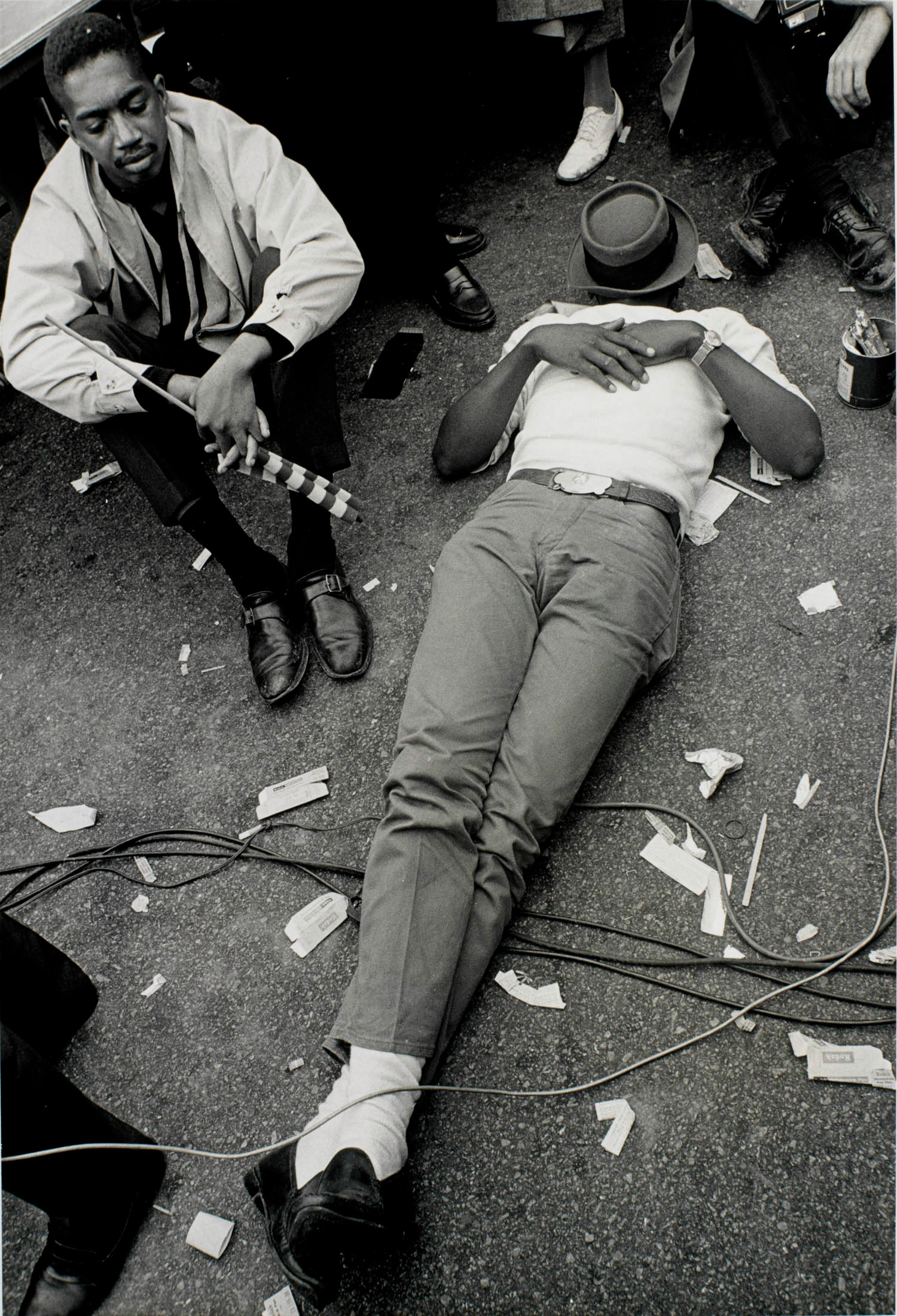

The fifty-four miles from Selma to Montgomery along Highway 80 in Alabama took marchers five days to complete. It was the largest civil rights demonstration the state had ever seen. Many who had never participated in the movement walked side by side with those who had been demonstrating for a decade. By the final leg of the march the number had swelled to some twenty-five to thirty thousand people. Almost every important news organization had reporters, photographers, and camera crews on the ground in Alabama, with personnel who were experienced in press coverage.11 Broffman made dozens of photographs along the route. He did his best work on the final day, when Dr. King led several thousand marchers into the heart of Montgomery up Dexter Avenue , past the Baptist church that had been his congregation during the Montgomery Bus Boycott, to the steps of the state capitol. This was the very building where George Wallace was sworn in as governor in 1963, vowing to keep Alabama segregated forever. As the crowds settled into position for the rally and speeches, Broffman captured the excitement and expectation of the assembled marchers as well as the fatigue and exhaustion brought on by five days on foot in difficult, damp conditions Plate 74.

Alongside Dr. King were several of the heroes of the movement, among them Rosa Parks, Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, John Lewis of SNCC, and Whitney Young of the National Urban League. Among the celebrities were writer James Baldwin and singer Joan Baez Plate 66. Morton Broffman produced affecting portraits of many of them. He seems to have learned that the audience could be as compelling a subject as the main event. His pictures of children milling around in the crowd, watching, waiting, and listening to the speeches Plate 77, Plate 78, are especially tender and intimate. Their faces are full of emotion and expectation, and of course their participation offered hope and the possibility that real and meaningful change may have finally come. In more than one photograph, Broffman singled out the children of Rev. Ralph Abernathy (fig. 19), who were there to witness this historic march on the Alabama state capitol. As one eight year-old marcher, Sheyann Webb, remembered: “It was like we had overcome. We had reached the point we had been fighting for, for a long time. . . . And if you were to just stand there in the midst of thousands and thousands of people and all the great leaders and political people who had come from all over the world, it was just a thrill. I asked my mother and father for my birthday present to become registered voters. They took me to the polls with them to vote.”12

The photography of the civil rights movement includes the work of great photographers but also simple and powerful images by photographers of modest aspiration and small renown. Sometimes the maker’s identity is unknown. These anonymous photographers have the occasional eye for the telling image, and by virtue of sheer numbers and their obvious industry their work warrants and repays study.

Expand image.

Standing in the middle of a nameless rural back road (fig. 20), one anonymous shutterbug, whose ideological beliefs would appear to be glaringly transparent, reminds us of how coherent and laser-like the camera can be in its articulation of time and space. The viewer is shuttled back in time to a scene of the kind that was responsible for taking hundreds of innocent lives. The window that photography justly claims to provide on the world also firmly demarcates our separation from that world. The French cultural critic Roland Barthes makes much of what he refers to as photography’s “umbilical” connection to its subject.13 According to Barthes, the reality offered by the photograph is not so much its truth-to-appearance as its truth-to-presence. The transcriptive and suggestive power of the photograph allows it to transcend mere resemblance and conjure a “subject”—to provide what Barthes calls a “certificate of presence.”14 This particular snapshot reminds us that some photographs of the civil rights era—no matter the circumstances of their production—are stamped with a disquieting, lingering aura that cannot be ignored. This is a medium that does best with things that are vanishing and which, we can only hope, no contrivance on earth can bring back again.

Citation

Cox, Julian. “Bearing Witness: Photography and the Civil Rights Movement.” In Road to Freedom: Photographs of the Civil Rights Movement, 1956–1968, edited by Julian Cox, 19–47. Atlanta: High Museum of Art, 2008. https://link.roadtofreedom.high.org/essay/bearing-witness-part-5-foot-soldiers/.